| Welcome to KUJmf |

KUJmf Society

- the odd track in the little town

|

|

| Welcome to KUJmf |

| The Society - KUJmf |

| The Railway - KURJ |

| KUJmf Vehicles |

| Links |

| ||

History:Some notes about Köping–Uttersberg–Riddarhyttans Railway

by Anders Nordebring

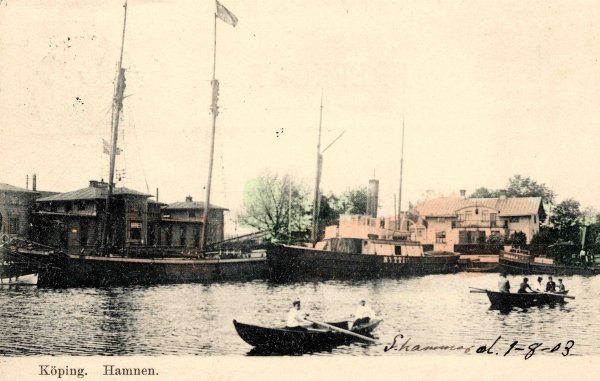

To the left the first KUJ station building in Köping, known as 'Byrån' (the Bureau) and today shared between KUJmf and the restaurant Athos. To the right the former railway hotel of KHJ, later living quarters for the traffic director of KUJ.

The main part of the shares in the railway company were acquired by a consortium in Norrköping, and later transferred to the city of Norrköping. These somewhat surprising acquisitions were founded on the for many years current plans for a railway between Köping and Katrineholm through Julita. If this line had been built, and an northern extension to Ludvika had been built at the same time, the harbour of Norrköping would have been an important shipping harbour for products from the province of Bergslagen. As late as 1930 a report recommended building the line to Katrineholm, preferably with KURJ broadened to standard gauge. Two daily passenger train connections between Riddarhyttan and Norrköping (changing in Katrineholm) was foreseen.

Nationalization and closing-downSince all plans for the Katrineholm line had been abandoned and the goods from Bergslagen hadthereby been finally secured by the harbour of Köping, the majority of shares was acquired by the city of Köping in 1931. In the late 1940s nationalization became imminent. The Swedish State Railways (in Swedish "Statens Järnvägar", SJ) had no real interest in incorporating KURJ (which by then as written above already was publicly owned), since this line did not have the character of a branch-line but instead that of a closed traffic system where most of the goods did not require transfer to other railways. There were also no gain for the public finances in it, since the odd gauge made impossible any coordination of e.g. rolling stock and repair shop resources. The nationalization was therefore mainly motivated by the parliament decision of 1939 about general nationalization of railways. The negotiations between the Swedish National Railways Board ("Kungl. Järnvägsstyrelsen") and KURJ were slightly delayed, but an agreement was signed in March 6 1952. The goods traffic was by this time still considerable, but in order to cut the foreseen losses the Swedish State Railways intended to close the remaining passenger traffic immediately after the take-over. The KURJ line was nationalized in July 1 1952, but His Majesty the King Gustaf VI Adolf represented by the Ministry of Transport and Communications did not authorize the closing of passenger traffic until August 22 1952. In the last timetable of KURJ, published in the national timetable periodical 'Sveriges kommunikationer' no 8 1952 valid as from August 1 1952, it was written that the KURJ timetable "could be changed at short notice", and in August 31 the last passenger train left. Mr Eve Östberg from Riddarhyttan had polished the steam engine for this last journey.

The Swedish State Railway building in Krampen. Photo from old postal card.

After the closing of passenger traffic the goods traffic, which mostly consisted of sinter and ore from Riddarhyttan to Köping, went on and modernizations were introduced in the form of small diesel engines and waggons for carrying loaded standard gauge waggons. In early 1960s a new industrial branch was built to Barkplan in Riddarhyttan. The last goods train from Riddarhyttan to Köping left in 1966, but the traffic by the Swedish State Railways continued between Köping and the iron works of Kolsva until 1968. An agreement was concluded between Riddarhytte AB and the Swedish State Railways in 1966, according to which Riddarhytte AB leased the line between Riddarhyttan and Krampen for a three-year period as from May 1 1966. For this traffic, consisting among other things of wood products and dross-wool, the company bought from the Swedish State Railways two small diesel engines and eleven waggons for carrying standard gauge waggons. This traffic, the last on old KURJ, ceased in the autumn of 1968. Incidentally, Krampen did miraculously keep its standard gauge passenger traffic until 1968, and the goods traffic for several years after that.

Passenger and goods trafficKURJ was in several ways a railway with a character of its own, not least because of the odd gauge, but also because of its old-fashionedness. While other railways introduced vacuum brakes and later on pneumatic brakes, it wasn't until after the nationalization the handbrakes were abolished from former KURJ. Unlike many others, the railway did not buy any motor-coaches, using steam engines for its passenger traffic to the end. The railway acquired modern passenger coaches by rebuilding some older coaches during the 1930s.

KUJ mixed train - the steam engine no 11, passenger coaches BCo1 16, Co1 13 or 14, BC2 12 - at the railway station of Köping in 1951. Photo from the collections of the Swedish National Railway Museum.

Even though the goods traffic was by far the most important for KURJ, the railway did tend to the passenger traffic as well. During the 1920s and 1930s passenger volumes declined, like on many other railways, because of the growing bus traffic; around 1915 KURJ had about 90.000 travellers while fully twenty years later this number was down to under 60.000. Besides buying shares in the local bus traffic the railway tried to win back passengers by building new halts. Thus came the halts of Karlsdalsvägen, Malma kyrka, Guttsta, Hagen, Hed, Oxbron, Uggelfors and Aronsberg into being. During the war years the number of travellers increased drastically for obvious reasons - in 1945 the passenger traffic peaked with 151.060 passengers going by KURJ - but after the restrictions on road traffic was abolished the buses took back the bulk of the passenger traffic in the Hedström Valley.

The railway line was kept in good order - compared to other narrow gauge railways in a very good order - and allowed a large-scale traffic of heavy ore trains. Comparing goods volumes KURJ more than held its own against comparable railways. KURJ also had a very favourable altitude profile; the line sloped downwards practically all the way from Riddarhyttan to Köping, which made it possible to haul heavy ore trains with comparatively small steam engines. The only important upward slope on the way down to Köping was the noted Forshammar slope, which began right before the station of Forshammar and continued to a point a bit north of the Aronsberg halt. This meant that many heavy trains were pushed over the Forshammar slope by an extra steam engine which afterwards returned to Riddarhyttan. While thinking about broadening to standard gauge KURJ had plans in 1916 for an alteration of the line in order to avoid the Forshammar slope while at the same time place Krampen on the main line, thereby dispensing with the shunting back and forth from Uggelfors, but it all came to nothing. Anyone who feels inclined to it can walk up the Forshammar slope on the embankment and still today note the rather steep gradient.

What is left?KUJ vintage train, the steam engine no 7 Patric Reuterswärd and the passenger coach BC 9, at their first exhibition place during the 1970s.

Besides the mostly intact embankment, there is quite a lot left of the railway. The station area of Uttersberg with station building (repainted in its old colours), platform, goods shed and turntable circle is rather well-preserved. Also the first station building of Uttersberg still stands, nowadays moved to Nyängen along the old industrial line to Östanfors. Nearby the bodywork of the inspection coach can be found as part of a summer cabin. Other buildings that can still be seen include the station buildings of Forshammar (moved to Allmänningbo and built together with another building), Karmansbo, Svansbo, Gisslarbo and Köping, the engine shed in Riddarhyttan, lengthman's cottages. In the old combined station building and office of the railway in Köping the KUJmf Society has its club premises. The Society also has at its disposal the steam engine no 7 Patric Reuterswärd, the passenger coaches BC 9 and BC1 10, trolleys and other objects from the railway. The first and the last passenger coaches of the railway are also preserved, by others: the Swedish National Railway Museum in Gävle has the very first passenger coach of KUJ, built by the railway's own repair shop in 1866, and the last passenger coach built for KUJ in Kalmar 1914 has after many turns ended up on the Danish island of Bornholm.

|

| |